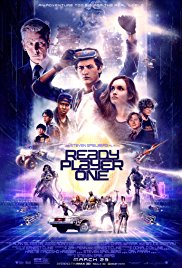

Join Other Player? (Ready Player One)

In a dystopian future, the whole of humanity apparently lives within about ten miles of each other and jump into a video game so they don’t have to look at each other. It’s not unlike the real world, except amplified.

2045 is a waking nightmare of abject poverty, corporate dependence, and debtors’ prisons. Respite comes by plugging into the largest, most diverse, and immersive video game/social network/escapism device ever devised, “The Oasis.” To make matters even more driving, the late inventor of The Oasis has hidden three keys (literal keys) within its many worlds. The first finder of all three of these keys can open a door and win the whole chocolate factory.

2045 is a waking nightmare of abject poverty, corporate dependence, and debtors’ prisons. Respite comes by plugging into the largest, most diverse, and immersive video game/social network/escapism device ever devised, “The Oasis.” To make matters even more driving, the late inventor of The Oasis has hidden three keys (literal keys) within its many worlds. The first finder of all three of these keys can open a door and win the whole chocolate factory.

Aimed at young adults, Ready Player One is not a terribly complex story. Aided by friends who are more skilled than he, a low-class hero uses his true belief in the game’s purpose and devotion to its creator to take on the big corporate giant trying to monetize The Oasis. That simplicity gives this movie room to be an exciting, with genuine feel good action moments. It balances the two realities—the real world and the game world—well, giving the sense of imminent danger and elation in ultimate triumph. The real world threats are the typical evil corporation type. They lock people up (in online labor camps); they send assassin drones after the hero, et cetera. Death in-game, however, has the horrible consequence of losing all your stuff, forcing a player to start over from zero—and that online currency has replaced actual money.

Ready Player One is full of references and tributes to pop culture, with special deference given to the 1980s. The film is nearly hyperactive at times shotgunning fan services in action sequences reminiscent of “survival mode” levels—resulting in a gamer nerdgasm. Other than the characters and a little world building, the screen has almost no original content. This isn’t a problem. It gives the audience a stream of feel good pills, which might be analyzed as a device to make statements about the addictive nature of game environments.

The biggest tribute/reference is the bad guy. Whether intended or accidental, the villain is straight out of a John Hughes film. He is a powerful authority figure, with unlimited resources, and yet he is completely undone by a collection of five “teenagers” (technically one of them is only eleven) and his own base level incompetence when fixated on a goal of questionable value.

The main characters shine though and are good strong characters. They are each two characters: their avatar and their real person. This duality of online life is reinforced throughout. The underlying societal message is clear: “Escapism is dangerous, and online life is explicitly designed to draw you in and keep you.” It is resolved in a YA reader kind of way, but that’s okay. This is a movie where you should feel good when everyone bands together for that moment when they do.

Take the time to enjoy Ready Player One.